How to Determine the Correct Shaft Length for Your Outboard Motor

When it comes to outboard performance, one detail that often gets overlooked is the shaft length. Choosing the right outboard motor isn’t only about horsepower or brand name. One thing that can make or break how your boat runs is the shaft length.

A shaft too short leaves your prop spinning in thin air.

A shaft too long drags the engine, slows you down, and burns fuel. People don’t realize this small mistake is what makes a boat ride sloppy, noisy, and inefficient.

This guide highlights every side and practical boatyard wisdom around shaft length. If you’ve ever wondered “Is my motor sitting too high?” or “Do I need a long shaft for choppy water?”, read this. We go through measurements, hull types, mistakes boaters make, and how to get it right the first time.

What Exactly Is Shaft Length?

Shaft length is the distance between the mounting bracket (where your outboard clamps on transoms) down to the anti-ventilation plate, sometimes called the cavitation plate. That’s the flat plate right above the propeller.

Why does this matter? Because the plate needs to sit almost level with the bottom of your hull keel when the motor is bolted. Too high, prop sucks air, you get cavitation, engine screams, but boat crawls. Too low, you drag extra metal, fuel gets chewed up, handling goes sluggish.

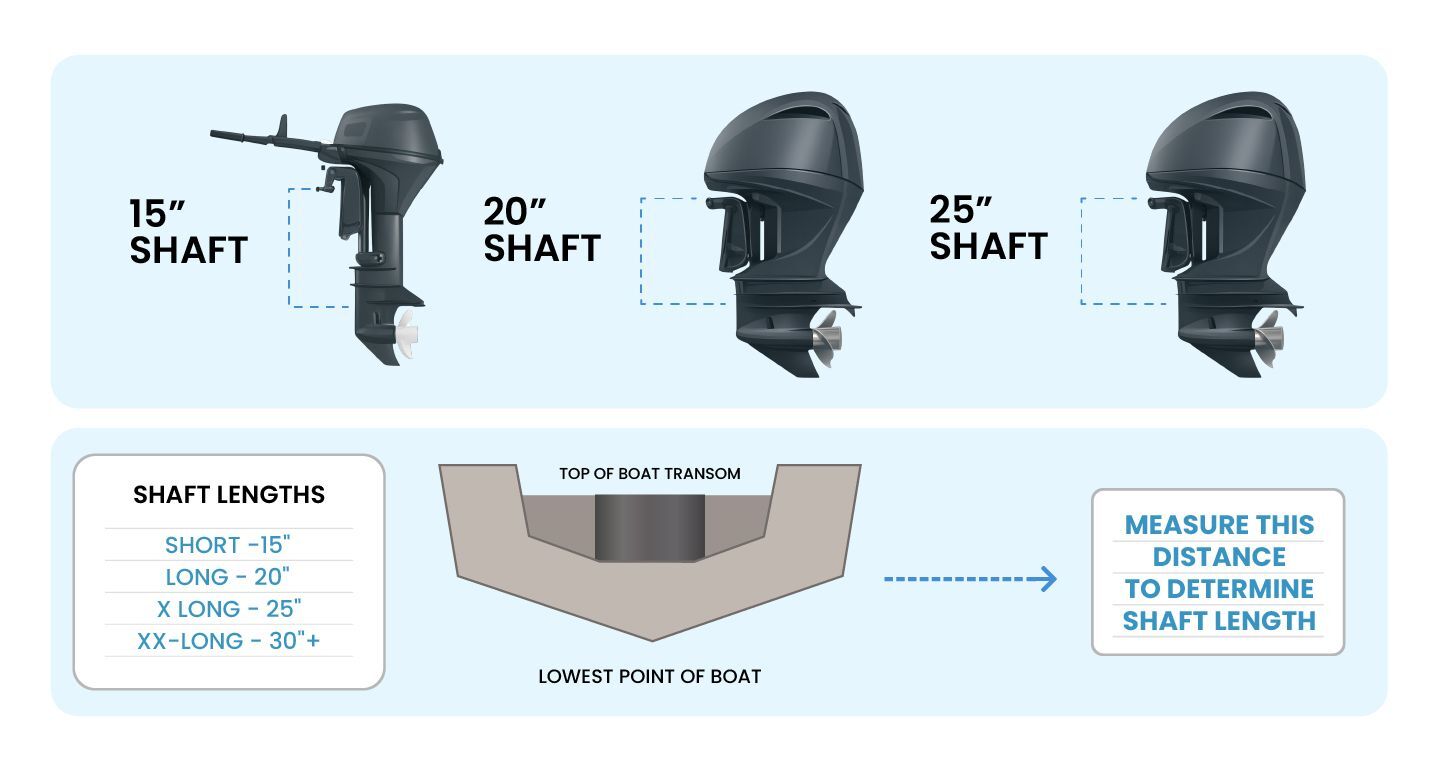

Industry standards break shafts into categories:

- Short shaft – usually 15 inches. Made for dinghies, inflatables, and small jon boats.

- Long shaft – 20 inches. Fits most mid-sized fishing boats, pontoons, and light runabouts.

- Extra-long shaft – 25 inches. Often seen on sailboats and larger cruisers.

- Ultra-long shaft – 30 inches or more. Heavy displacement hulls, ocean sailboats.

Important thing, these are nominal lengths. A “20-inch” shaft from Mercury may actually measure closer to 21 or 22. Yamaha might be a little different. So don’t rely on the label.

Why the Correct Shaft Length Matters?

Think of shaft length as setting the geometry between hull and propeller. Wrong geometry leads to:

- Cavitation / Ventilation – propeller spinning in bubbles instead of water. Causes vibration, noise, and lost thrust.

- Fuel inefficiency – the engine works harder, consumes more gas.

- Poor handling – bow rise, porpoising, difficulty getting on plane.

- Engine wear – strain on gearcase, overheating from poor water intake.

If you have ever seen a boat motor throwing rooster tails of spray instead of clean thrust, odds are the shaft length or engine mounting height is wrong.

Step-by-Step: How to Measure for Shaft Length

Below is a detailed process you can follow in the driveway or in the yard. Measure the boat (transom height), optionally measure the motor (actual shaft), then translate those numbers into the right choice, considering chop, load, hull, and mounting hardware.

Step 1: Measure the Transom Height

- Stand at the center of your boat’s transom. That’s the flat back wall where the outboard hangs.

- Put your tape at the lowest point of the keel (the dead bottom in the middle of the hull).

- Pull it straight up, vertical, not along the angle of the transom, until you hit the top edge where the motor clamps or bolts.

That number is the true transom height. Most small skiffs and dinghies land near 15–17″. Mid-range fishing boats run 18–22″. Sailboats or offshore rigs can go up 25″ or even more.

Common Mistake To Avoid: People measure along the slope, which gives them 2–3 inches extra, then they buy the wrong motor. Don’t do it. Keep it straight.

Step 2: Match With Standard Shaft Lengths

Once you have got your transom height, you compare it with standard outboard shaft categories:

| Transom Height | Recommended Shaft |

| 14–17″ | Short Shaft (15″) |

| 18–22″ | Long Shaft (20″) |

| 23–27″ | Extra-Long (25″) |

| 28″+ | Ultra-Long (30″) |

This is the baseline chart used in every boatyard. It ain’t fancy, but it works.

Step 3: Adjust for Your Conditions

Charts are fine, but boats don’t run on paper; they run on water. You need to account for where and how you ride:

- Rough water/chop: Add a bit more length. Waves lift the stern, prop can break free.

- Heavy load: Extra gear, fuel, and batteries push the stern down. The shaft should reach deeper.

- Hull design: Planing hulls like to sit higher, while displacement hulls (like sailboats) need extra-long shafts for constant prop bite.

Think of it this way: if your boat lives on calm lakes with a light crew, the chart number is enough. If you’re running offshore with four buddies, a cooler, and a big tackle box, you'd better size up.

Step 4: When in Doubt, Go Longer

This one comes from real boatyard grit: if you’re stuck between two shaft lengths, always go for the longer one. Why? Because you can adjust down. A jack plate or mounting holes let you lift the motor an inch or two. But a shaft that’s too short? Nothing fixes that; it’ll cavitate all day and ruin the ride.

Step 5: Confirm with Manufacturer Specs

Last, check the builder’s manual. Boat makers often give exact shaft recommendations. Outboard brands like Mercury, Yamaha, and Suzuki all list ranges. For example, Mercury lists 14–17.5″ as short, 18–22″ as long. That extra detail keeps you from buying the wrong gear.

Considerations Most People Miss While Measuring Shaft Length

Boats are not all built the same, loads shift, motors weigh differently, and conditions change. If you stop at a single number, you set yourself up for frustration. Below are the extra things the seasoned hands check before saying that’s the right shaft.

1. Boat Type Matters

Inflatables and RIBs, most have shallow transoms. A short shaft 15″ works fine. But some high-pressure floor inflatables ride deeper and need a 20″. Many folks miss this and end up with prop wash.

Pontoons, the twin tubes ride higher, but the engine mount bracket usually hangs down lower than you expect. Long shaft is almost always the call.

Sailboats, displacement hull, heavy keel, and deep waterline. These boats want extra-long or even ultra-long. Otherwise, every time the stern lifts in a swell, your prop comes gasping air.

Don’t think one chart number covers all these hull shapes.

2. Engine Weight & Design

Four-stroke engines are heavy. That big block sits on the transom, stern sinks lower in the water. A transom measured at 20″ on dry land might act like 22″ when the boat is loaded. Two-strokes being lighter don’t sink her as much. That’s why mechanics often say, Know your motor weight before final call.

Learn the Difference Between the 4-Stroke and 2-Stroke Outboard Motors.

3. Load and Weight Distribution

Another thing boaters ignore: how the boat sits when it’s actually rigged. Fuel tank, livewell full of water, three buddies sitting shaft, your stern drops 2–3 inches easily. If you only measured dry, your shaft ends up short. Better to measure with the typical load on board, or add a few inches to be safe.

4. Water Conditions

Flat inland lake is forgiving. Ocean chop or river current isn’t. In rough conditions, your stern bounces, motor lifts, and prop ventilates. That’s when having the shaft an inch or two longer saves the day. Don’t just measure for calm. Measure for the worst case.

5. Electric vs Gas Motors

Trolling motors, electric outboards, they follow different rules. The prop must sit a minimum of 12 inches below the waterline to stay quiet and efficient. Electric brands like Minn Kota, Torqeedo list specific shaft ranges. Gas outboards, less sensitive, but still need a cavitation plate aligned with the keel.

6. Between Sizes? Go Long

Say your transom height sits right in the middle of two sizes, like 21.5″. A shorter shaft may work in flat water, but it will bite you in chop. Extra length is always safer. You can lift an engine up a hole, or use a jack plate. But nothing fixes too short. That’s dead wrong from the start.

Common Mistakes Boaters Make

This is where people mess up:

- Measuring at the wrong angle: Some measure along the sloped transom instead of straight vertical. That gives the wrong number.

- Assuming “long shaft” is always 20 inches: In reality, it could be 19 to 22, depending on the brand.

- Ignoring water conditions: A boat that runs fine in a calm lake may cavitate badly in ocean chop if the shaft is too short.

- Over-relying on jack plates: Yes, you can raise or lower the engine a bit. But don’t expect a 15″ shaft to run right on a 22″ transom. Physics won’t bend.

- Buying before measuring: People buy used motors on deals without checking the shaft, then wonder why the performance is garbage.

FAQs

What happens if your outboard shaft is too long?

A too-long shaft drags deeper in water, causing extra drag, poor speed, reduced fuel efficiency, and rough handling. Boat balance and performance usually get compromised heavily.

Is a 20-inch transom a long shaft?

Yes, a 20-inch transom is typically classified as a long shaft. It’s a standard size for many mid-sized boats, giving good prop placement and steady performance in most conditions.

What happens if you put a long shaft outboard on a short transom?

Mounting a long shaft on a short transom makes the motor sit too low, drowning exhaust, creating spray, cavitation, and unstable handling. Fuel burn increases while performance and safety take a hit.

Need Help Choosing the Right Shaft Length?

When shopping for a new or used outboard motor, one of the most important, and often overlooked, factors is the shaft length. Choosing the correct shaft length ensures your boat and engine perform efficiently, keeps your boat safe, and prevents unnecessary wear and tear. In this post, we’ll break down what shaft length means, why it matters, and how to measure your boat to find the right fit.

Our team is here to help you match the perfect outboard to your boat. Contact us at 270-618-5200 anytime for expert advice or check out our selection of used outboards.

Happy boating, and stay safe on the water!

Posted by Brian Whiteside